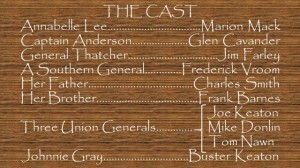

Posted as part of the Third Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon hosted by Silent-ology

The General has, as a movie, received a lot of thumbs up. Roger Ebert credited it with “a graceful perfection”, it currently sits at number 34 in Sight and Sound’s (interestingly silents heavy) critics’ poll of the greatest movies of all time and was amongst the first batch of movies inducted into the National Film Registry for preservation by the Library of Congress no less.

As a piece of cinema, then, its reputation seems (despite the well documented ambivalence of audiences in 1926) assured. But what about as a historical document?

I was certainly unaware until I read more about Buster’s career that The General is actually based on a real Civil War incident – namely, the Great Locomotive Chase of 1862. Buster and his collaborator (credited as co-director, somewhat generously by all accounts, including his) Clyde Bruckman based the movie on ‘Daring and Suffering: A History of the Great Railway Adventure’ written by one William A. Pittinger – an active participant in the day’s events (although not, as it turns out, necessarily a wholly reliable narrator).

As a Brit whose Civil War knowledge was roughly equivalent to that demanded by Apu’s citizenship test, this came as something of a surprise. But it did light a spark of curiosity, just how accurate is it?

All of the named characters (with one obvious exception!) seem to be based pretty much directly on real people.

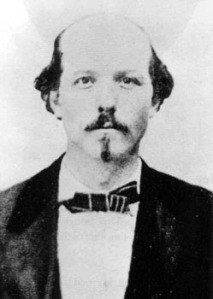

For Johnnie Gray, read a Mr William Allen Fuller, conductor of The General on the day in question. In reality, he was not the only member of the crew to take up the chase (being accompanied by Anthony Murphy (foreman of motive and machine power) and E. Jefferson Cain (the engineer)). Amalgamating these three to one character makes perfect cinematic sense and I get the feeling that Mr Fuller would have wholeheartedly approved, given he seems to have made vigorous efforts to talk up his role at the expense of Murphy and Cain’s.

William A. Fuller. See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

You can see the movie star quality right there. Great hair.

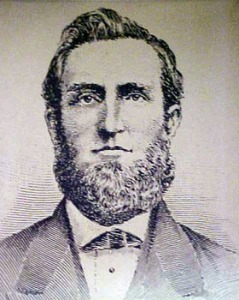

On the Union side, ‘Captain Anderson’ stands in for James J. Andrews, leader of the group subsequently dubbed ‘Andrews’ Raiders’ but in fact not a captain or indeed a soldier at all. Andrews was something of an adventurer having been engaged in the (highly profitable) business of running quinine (lots of bugs in Mississippi) from North to South despite (or, depending on your point of view, because of) the Northern blockade. He did use this position to gather information for the Yankees, but it seems unclear whether he felt any great allegiance to one side or the other or whether he was simply engaged in profitably playing one side off against the other.

Andrews’ motives for planning the raid are likewise somewhat opaque, with varying accounts of how much he expected to be paid for its successful completion. For all that, though, he conducted himself with considerable daring during the raid and even more dignity in its aftermath. There’s a great movie waiting to be made about him too.

James J. Andrews. See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Thus, far, looking pretty good!

Hmm, yes. Perhaps not unexpectedly there’s no record of any romantic complications of any kind. Still, Johnnie doesn’t even know his girl’s on the train until he gets to Union territory (which, as we’ll see, never happened anyway). So, you know, whatevs.

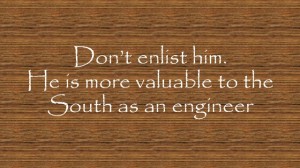

Spectacularly back on track[1] here though. In the movie, Johnnie tries to enlist with the Confederate army but is rejected because (unbeknownst to him) it’s decided that keeping the railroad running is more valuable than one more soldier.

Allowing for a little compression for dramatic purposes, on this point Buster is wholly accurate. William Fuller did almost joint a militia, but the governor of Georgia proclaimed that experienced railroaders should stay at their posts rather than joining up. A wholly sensible decision given how critical the railroads were to both sides as really the only practical means of moving men, supplies and equipment the vast distances involved in fighting the Civil War.

[1] Weak pun intended

In terms of timing, spot on again! The attack on Fort Sumter, generally seen as the start of the war, occurred on 12 April 1861, whilst the Andrews Raid (pleasingly for fans of symmetry and writers of silent movies intertitles) was a year to the day later.

The intertitles for Anderson/Andrews’ tête-à-tête with Thatcher/Old Stars gives a brief, but pretty accurate, summation of the plan, such as it was, with the ultimate aim being the capture of Chattanooga, TN., a critical hub for pretty much all Confederate rail traffic from West to East.

Quite who ‘General Parker’ represents is a little less clear. Best guess, a General Don Carlos Buell, Old Stars’ immediate superior who had around 60,000 men in Tennessee at the time. However, expecting him to seize the day on a moment’s notice might have been a trifle optimistic. DC was a cautious fellow, once boasting that he had “studiously avoided any movements which to the enemy would have any appearance of activity or method.” He was hardly alone in this. Indeed, it seems that Abe Lincoln spent a not inconsiderable amount of his time early in the war fielding explanations from various commanders of why they simply could not advance against less numerous Confederate forces. No wonder he looked so grumpy.

And yes, they did make their way south to Atlanta by pretending to be Kentuckians looking to join the Confederate Army. This seems to have involved affecting big ol’ Southern accents (I’m thinking O’ Brother Where Art Thou?, but then I think everyone in Minnesota sounds like Marge Gunderson so I’m probably not the best judge) and, after one close shave, swapping some blue Union army trousers for a less conspicuous yellow striped number. If anything, this charade seem to have been too convincing, given that two of the party actually ended up joining a Confederate artillery unit.

The actual theft of The General is almost eerily spot on, historical accuracywise.

- Yes, it was at the marvellously named Big Shanty

- Yes, it was during a meal/refuelling break

- Yes, Andrews and Co did just drive away, unchallenged until Fuller (and Murphy and Cain) went running after them.

- Yes, the pursuers did set off thinking it was cowardly deserters, not beastly Northern raiders who had nicked their train.

The movie does swap breakfast for dinner, in fact the journey was so early that two of the raiders overslept and missed their 5am (!!) departure from Marietta. For perhaps understandable reasons, the reported jeers and laughter of the crowd, along with helpful suggestions along the lines of ‘get a horse’ are not included. We may be divided by geography and time, but unhelpful wiseacres are universal.

The chase itself is also surprisingly true to history, at least up to a point. The pursuers really did progress through a variety of means of transport, including a hand car (although rather than the ‘see saw’ type thing we see in the film, it was apparently a weird sort of gondola arrangement propelled by pushing poles along the ground), which really did hit a break in the rails and tumble into a ditch. The raiders really did throw all manner of stuff, including sleepers, on the track in a bid to slow them down. No one seems to have sat on the cowcatcher and bounced them out of the way, although Fuller did, somewhat unconvincingly, claim to have pulled one (weighing in at about 900 pounds) out of the way on his own. Fuller and co really did give chase on the Texas (in reality, following stints on the Yonah and the William R Smith).

Moving on, the raiders really did pass up opportunities to engage their pursuers in the mistaken belief that they were more numerous and better armed than was in fact the case and the chase did in the end become a question of who ran out of wood and water (both of which a 19th century locomotive consumed in heroic quantities) first. After reaching the almost unbelievable speed of 60mph [insert wry observation about the probability of a modern British train achieving such a feat], the General finally ran out of both (in fact, you might say it ran out of steam!![1]) about 15 miles from Chattanooga. At which point, Andrews and the rest of the raiders headed for the hills.

By Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel (book authors). [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

[1] I’m sorry

So, up to a point, impressively accurate. However, sadly for history (but gloriously for cinema) after a point Buster diverges from the facts completely. Fuller never left Confederate territory and there was no chase back towards Atlanta, which means no trains crashing through burning bridges (in reality, the Texas remained in service until the early 20th century and The General has pride of place to this day in the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History).

Western and Atlantic Railroad No. 3 ‘The General’ on display in Kennesaw, Georgia. [Photographer Harvey Henkelman via Wikimedia Commons]

In reality, after fleeing the scene the raiders were captured, imprisoned and in eight cases (including Andrews himself) hanged as spies. Eight more escaped and the remaining six were later exchanged for Confederate prisoners. 18 of the Andrews Raiders (including the two sleepyheads, but not Andrews himself as a civilian) subsequently received the Congressional Medal of Honor – amongst their number the very first recipients of the United States’ highest military honour. These basic facts, though, skim over a number of prison breaks, flights through hostile territory (possibly the inspiration for Buster’s rainy night with a bear) and no small amount of controversy. You could make a dozen movies about this stuff.

Up to a point, The General stays close to history, often strikingly so and whilst the second half of the movie is fiction (as Keaton later said “the original locomotive chase ended when I found myself in Northern territory and had to desert. From then on it was my invention, in order to get a complete plot.”), this comedy still scores way, way higher than many ‘serious’ historical films (I’m looking at you Braveheart and Anonymous).

By No machine-readable author provided. Emilio Kopaitic~commonswiki assumed (based on copyright claims). [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“Historians from England will say I am a liar”

Indeed they will, Mel, on account of all the lying.

If anything this little exercise has made me admire the film and its maker even more. You could make a number of movies from the source material, from a number of perspectives – Buster took far from the most obvious and made, if not the best possible movie, something pretty damn close. Bravo, sir, bravo.

| Wanting more?

This is, inevitably, a very quick canter through a long and fascinating story. If you want to fill in some gaps, I can heartily recommend ‘Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and the First Medal of Honor’ by Russell S. Bonds (available from Westholme Publishing). If, on the other hand, you fancy reading something along these lines but written by an actual historian who actually knows what they’re talking about, might I point you in the direction of Reel History (Atlantic Books) by the brilliant Alex von Tunzelmann? |

Sources:

- Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and the First Medal of Honor – Russell S. Bonds, 2007

- The American Civil War – John Keegan, 2009

![keatonmack By Buster Keaton (screenshot) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://specialpurposemovieblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/keatonmack.png?w=166&resize=166%2C231&h=231#038;h=231)

Pingback: The Third Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon – Celebrating 100 Years of Buster! | Silent-ology

Wonderful article. America’s Civil War is a fascinating study. I first learned of the locomotive incident through a Disney film seen in my childhood. The premise was exciting, but that movie was a bit on the boring side (The Great Locomotive Chase, 1956). Buster not only made a wonderful movie, but he piques the interest in history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I feel that I should give the Disney movie a go, probably more for academic interest than any expectation of quality though.

Still, I’ve seen How to Stuff a Wild Bikini so that won’t be anything new!

LikeLike

Hi there, thank you for all this helpful research! Buster was always extra proud of THE GENERAL, precisely because it was based on real history. A serious work of art, you see. I was the most surprised to read that the chase itself was surprisingly accurate–that’s the kind of sequence you’d assume was mostly comic invention.

Thanks for participating in the blogathon!

p.s. Ha ha, we don’t ALL sound like Marge Gunderson up here! 😉 (Actually I haven’t heard anyone who sounded exactly like her, but that’s for another discussion!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, thank you for hosting it so wonderfully!

Yah.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic research and review. I love learning how the art Stands up against the facts. You made excellent points that I will have to come back and re-read. By the way, I understand your jab at Gibson’s historical interpretations but that movie did help the movement to an independent Scotland… Again, wonderful post😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tom. “This site was born for the sole purpose of participation in the fabulous Silent-ology’s Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon…” Wow. That is dedication. I enjoyed reading your findings about the historicity of The General. I’m happy to know that I am not the only person who likes the name Big Shanty. If I lived in Kennesaw, Georgia, I would launch a campaign to change the name back to Big Shanty.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂 I’ve broadened my horizons slightly since then (not as much as I’d like, but life gets in the way), but Lea’s Blogathon still feels like coming home!

LikeLike

Wow, this was fascinating! I had no idea this was based on an actual event and it is pretty amazing how close to fact he stayed. Usually, I remain deeply skeptical of anything I see on film, but his attention to detail is inspiring. Would that more filmmakers would take him as an example.

And it’s impressive how he was able to make comedy (as opposed to drama) out of a real historical event. Really appreciate your research and post on the topic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article, very fun to read, and fascinating to learn more about The General.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m another one who didn’t realize this film was based on actual events. Your comparison between the film and the historical events should be included as a Bonus Extra on a DVD release. I’m serious!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😳 You’re too kind sir!

LikeLike

Thank you for this fascinating study of The General! I’ve known that it was based on an actual event, but I hadn’t been aware of how faithful Keaton had been to much of the story. This article has piqued my curiosity to learn more about the Andrews raid.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! As I said, I’ve really only scratched the surface here, there’s so much more to the story. Real Boy’s Own stuff!

LikeLike

Amazing idea! A very interesting and imformative article. I will probably think about all you said next time I’ll watch The General.

LikeLike

It’s been said that The General has the feel of a Matthew Brady photograph. I think Buster’s authenticity goes a long way in making this happen. Your article makes me have even more respect for him (if that’s even possible.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed! I was thinking mostly about the content, but you’re right that the spot on set design, props etc hugely contribute to the accurate feel as well.

Thank you!

LikeLike